1998

|

Whitney 7, Natalie 8

|

I stared at the ZipLoc bag, clouded with moisture. Inside

were muddy shoes. I had placed them there for the dogs to sniff so that they

would have the girls scent. By the time they called in the dogs the temperature

was dropping rapidly and Natalie was only wearing a sweatshirt.

Why hadn’t they found them? It had been four hours and the

helicopter had circled the area with their loud speakers shouting, “Natalie and

Whitney Esson, age 7 and 8. If you see them, please call the sheriff’s office.

Natalie and Whitney, we are looking for you. Stay in the open.” .....The air is

frigid.

Right after lunch, we

were deep in conversation with an animated missionary friend up in the

mountains. Natalie and Whitney kept tugging at me asking if they could go to

the top of the mountain. Finally, not wanting to miss out on our friend’s

adventures in South America, I quickly say, “Yes, yes, go ahead, but be

careful.” I thought they meant the top of the hill behind the cabin. They

meant..."the top of the mountain.” Alicia who was ten stayed to hear the

stories.

Half an hour later, I send Alicia trudging up the hill to

check on them. They are nowhere in sight. Jim and I feel vaguely concerned so

huff and puff up the hill calling loudly. There is a pretty steep drop off at

the top and our eyes scan the brush below. We decide to follow the path. Muddy

ravines stretch out continually to our left and numerous paths go off to the

right as we hurry faster scouring the cliffs.

We search for an hour shouting their names repeatedly and

more desperately. Worry runs through me like a current. I realize how easily

you could lose your way as we hurry back with nothing clearly marking the many

winding paths in these torn hills.

I remember the waitress at the donut shop who said this

mountain has the highest percentage of child molesters of any place in

California. The girls are level headed so it’s not the getting lost that scares

me. I am praying now with more urgency. Jim calls the sheriff and our friends.

I’m caught somewhere between incredulousness, embarrassment

and terror. I look totally calm and collected, however...well, maybe a little

mist in my eyes. Two fixed wing aircraft are now searching and one helicopter.

Ground crews have been unsuccessful. This can’t be happening.

Jim makes me stay at the cabin with a deputy and our

missionary friends who alternately pray with me and reassure me with many

stories of God’s faithfulness in their lives. There’s a knock at the door and

an eager ranger type wants clothes or shoes for the dogs to sniff. Another

knock and two female trackers, awfully young I notice, want me to identify the

girls' footprints in the mud around the cabin to help in their search. I get

the feeling this is their first 'for real’ search. It is almost dark now and

the crackle of the deputy’s radio tells us the girls have not been found.

I’m shivering inside the cabin and wondering why they can’t

find two small girls in such a small area. Strangers are kindly out combing the

hills. The radio startles us. A man on a tractor, clearing land had seen two

girls walking earlier.

“Where can they be?” I ask lamely. The deputies are

obviously perplexed. We hear the helicopter but it will soon be too dark to

see. I am still not panicky but I wish Jim would return. He is still out

there. I walk outside. The needle sharp

wind stings my eyes. A police car arrives.

A friend confides she thinks they may have found them but

they aren’t allowed to say. A little girl has called 911 from a pay phone in

front of a liquor store and said she is lost. We wait. Yes, there are two

girls. They have been walking for hours looking for civilization and a pay

phone. I’m more than misty now.

Jim is not back. A crowd is gathering. Another police car

arrives and in the back seat sit two of the most precious little girls I have ever

seen. I snatch them from the car and strangle them with hugs. The officer says

they too have been praying. “The guys were pretty worried,” he says, giving me

a knowing look.

I’m amazed at all the Christians in this ‘heathen place’ the

waitress had described. Whitney’s words rush out with a worried look, “Mom, we

didn’t talk to strangers but we did wave to a lady with a dog.” I see Jim

coming now, disheveled and breathless. His face is drawn and white from four

hours running, walking, shouting, and agonizing for his daughters.

We stood in a ragged circle. We thank God for the men on the

police force and the dedication of the search and rescue team. The crowd thins.

Natalie confides, “We sat down on the path, held hands and prayed six times,

Mommy." "We walked and walked in the mountains until we came out on a

road with a yellow line.” She took a deep breath and continued, “I took off my

sweatshirt and let Whitney use it for a pillow and we rested by a giant stump.”

Natalie adds that a policeman drove by and she put up her

hand for him to stop but he just waved. I smile thinly. Whitney interrupts with

a frown and whispers, “We saw a man on a tractor. He left his magazine and we

picked it up, but we threw it back down cause it had bad, bad pictures.”

Natalie chips in, “We looked for a pay phone forever. I

carried Whitney piggyback to keep her warm.” Whitney then divulges, “When we

finally found the pay phone Natalie told me to be quiet and let her do all the

talking.”

Our missionary friends sent us the front page headline from

the Big Bear Grizzly after we returned home. It said among other things:

8-YEAR-OLD KNOWS WHAT TO DO IN EMERGENCY - CALL 911

“Some 20 searchers from the Sheriff’s station, Search and

Rescue, Posse, on foot, horseback, motorbike and in a helicopter and

all-terrain vehicles, combed the East Valley for some five hours. Meanwhile,

the girls recognized that they were lost, found their way to Big Bear Blvd. and

walked to the Liquor Junction store where they called 911 from a pay phone. The

girls were unharmed.”

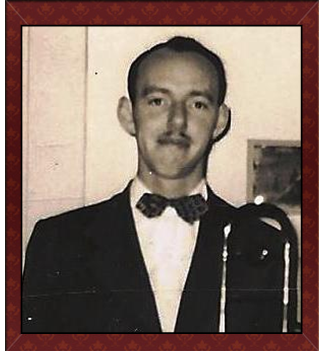

Daddy played the slide trombone. If

you were sitting in the front row of the small church he pastored in 1992, my

husband Jim jokes that you had to duck when he started sliding wildly at the

fast parts of a song. The soaring vibrato from his trembly wrist as he

pumped that slide with blatant enthusiasm to a glorious crescendo,

sparked fervor into the hearts of his straggly

congregation. The pianist bobbed her considerable girth in a

dramatic and savage attack on the keyboard.

I always wonder why pianists think body movements enhance piano performance. A few of the faithful leap

to their feet and clap. An Amen carries

from the back row.

Daddy played the slide trombone. If

you were sitting in the front row of the small church he pastored in 1992, my

husband Jim jokes that you had to duck when he started sliding wildly at the

fast parts of a song. The soaring vibrato from his trembly wrist as he

pumped that slide with blatant enthusiasm to a glorious crescendo,

sparked fervor into the hearts of his straggly

congregation. The pianist bobbed her considerable girth in a

dramatic and savage attack on the keyboard.

I always wonder why pianists think body movements enhance piano performance. A few of the faithful leap

to their feet and clap. An Amen carries

from the back row.

To get back to the point of this story; I’m

drawn like a magnet to thrift shops. I ducked into one along 9th

Ave. in Pensacola last Thursday and there was a sawn-off pew the size of a wide

chair with bright red upholstery between the rich wood arms, perhaps a small

exaggeration. The hymn holder and round holes for communion glasses were still

perched jauntily on the back. I showed amazing restraint pausing just long

enough to sit in it quickly and surmise it was surprisingly comfortable.

To get back to the point of this story; I’m

drawn like a magnet to thrift shops. I ducked into one along 9th

Ave. in Pensacola last Thursday and there was a sawn-off pew the size of a wide

chair with bright red upholstery between the rich wood arms, perhaps a small

exaggeration. The hymn holder and round holes for communion glasses were still

perched jauntily on the back. I showed amazing restraint pausing just long

enough to sit in it quickly and surmise it was surprisingly comfortable.

.png)