Daddy played the slide trombone. If

you were sitting in the front row of the small church he pastored in 1992, my

husband Jim jokes that you had to duck when he started sliding wildly at the

fast parts of a song. The soaring vibrato from his trembly wrist as he

pumped that slide with blatant enthusiasm to a glorious crescendo,

sparked fervor into the hearts of his straggly

congregation. The pianist bobbed her considerable girth in a

dramatic and savage attack on the keyboard.

I always wonder why pianists think body movements enhance piano performance. A few of the faithful leap

to their feet and clap. An Amen carries

from the back row.

Daddy played the slide trombone. If

you were sitting in the front row of the small church he pastored in 1992, my

husband Jim jokes that you had to duck when he started sliding wildly at the

fast parts of a song. The soaring vibrato from his trembly wrist as he

pumped that slide with blatant enthusiasm to a glorious crescendo,

sparked fervor into the hearts of his straggly

congregation. The pianist bobbed her considerable girth in a

dramatic and savage attack on the keyboard.

I always wonder why pianists think body movements enhance piano performance. A few of the faithful leap

to their feet and clap. An Amen carries

from the back row.

By then, all Daddy had left was a fringe of

white hair around the edges of his shining earthly crown. The dominant feature

of that face below the sagging nose was his wide smile with those big square

teeth, a little crooked which I inherited. Adams apple moving up and down in

preparation, he had a habit of pausing during the sermon for an interpreter to translate

his Swahili into Nandi or Kikuyu, as if it was 1960 and he were still in East

Africa. Of course, the church was in Florida and he was

speaking English. He was paid no salary, and offerings were so small that

he had to build his own small podium that I have today. I use it

for a bookcase in the bedroom. “It could be Holy,” I have tried to

explain to Jim.

|

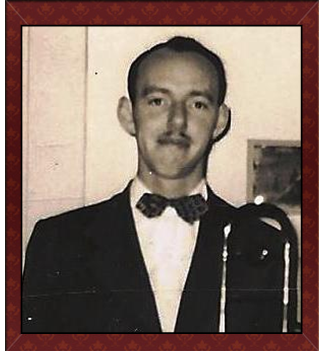

| My Dad |

| |

| Rhett Butler |

My parents bought the 10,000 sq. ft. former Alger-Sullivan sawmill office near the railroad track in Century, Florida for a song. It had rich wood wainscoting throughout, weathered wood floors and ceilings reaching to 18 feet. “It has possibilities,” enthuses Dad as he and Mom lean over the black iron fire escape in back. They planned to turn this albatross into a southern mansion complete with four big columns out front and a winding staircase to the second floor. They did actually hang a crystal chandelier and did endless repairs but the staircase never materialized. Mom always imagined that she was Scarlett from “Gone with the Wind” and Daddy, Rhett Butler. The only similarity was the mustache. The sawmill came with a sagging hotel next door, the “Century Hotel.” My sister and I still joke about who finally gets the fountain which was in front, a small boy, with water streaming forth.

After Daddy died and Mom sold the house, I

chose the podium (see first paragraph), family pictures, the “Africa trunk”

which is in the foyer of our home and the grand piano that has a cracked

soundboard, but sounds good except for the three low keys. The

antiques, which Mom loved and “silver service” went to my siblings, the famous

trombone to my oldest brother, incidentally, the only one of us that “turned

out right.” The rest, mostly remnants of Dad’s hardware store like

books of paint samples and carpet squares, we surreptitiously tossed from

the second story window into the waiting arms of a blazing fire in the side

yard between the former sawmill house and the hotel, (not the fire escape

side).

We saved some of their old letters from Kenya, back when people

used carbon paper in the typewriter for every piece of correspondence.

They had been painstakingly hole-punched and put in big blue folders which had

faded into an unattractive shade of splotchy purple. Much, sadly, we

threw away but I saved two boxes of their letters, in case I wanted to write a

book.

We saved the leather football helmets and

soiled uniforms from some team sponsored by the lumber mill years before, for

the “antique road show.” They have since strangely disappeared.

To get back to the point of this story; I’m

drawn like a magnet to thrift shops. I ducked into one along 9th

Ave. in Pensacola last Thursday and there was a sawn-off pew the size of a wide

chair with bright red upholstery between the rich wood arms, perhaps a small

exaggeration. The hymn holder and round holes for communion glasses were still

perched jauntily on the back. I showed amazing restraint pausing just long

enough to sit in it quickly and surmise it was surprisingly comfortable.

To get back to the point of this story; I’m

drawn like a magnet to thrift shops. I ducked into one along 9th

Ave. in Pensacola last Thursday and there was a sawn-off pew the size of a wide

chair with bright red upholstery between the rich wood arms, perhaps a small

exaggeration. The hymn holder and round holes for communion glasses were still

perched jauntily on the back. I showed amazing restraint pausing just long

enough to sit in it quickly and surmise it was surprisingly comfortable. It was large enough to accommodate a preacher the size of Hagee or someone

important like Billy Graham. Now in my eyes, my Dad far surpassed either

of those men and skinny as he was in the end, I could imagine him in this

throne-sized pew. Who knows, it could be as holy as the aforementioned

podium, now bookcase. I showed amazing restraint plus the fear that Jim

would kill me. I did not purchase the pew-throne.

Yesterday back on 9th Ave., I found myself

veering wildly into the parking lot of the “Teen Challenge Thrift Store” to see

if it was still there. It sat affixed with the orange sticker for $10.99

among the soiled couches and scratched coffee tables arranged in the glaring

light of “today only” bargains near the front windows. I sped-walked so

as not to be obvious and let the cashier know I wanted it. I was amazed

no one else had snatched this treasure.

Feeling impulse-shoppery, I

spied the gaudiest oriental chest with brass hardware (well, it could have

been) beside the checkout that I thought would be a great sewing cabinet

instead of the cracked plastic green thread holder I use now. It used to be

Mom’s, now that I think about it. I asked for the manager and pulled out

all my overseas missionary haggling skill and the price was dramatically reduced.

I am really not an impulse buyer, but I felt uncharacteristically and

unflinchingly audacious. I got those two words from the hardback

Thesaurus they threw in for 25 cents.

Two previously “challenged teens” loaded

the treasures into the Honda. I could not close the trunk, but the

pew-throne was so heavy, there was not a chance it would fall out. I

thought the young man with the blue tattoos and strings of greasy blonde glued

to his skull was snickering, but I chose to ignore him.

Inching around the curves down Scenic Hwy.

with the big red throne-pew hanging precariously from the trunk, a sizable

parade formed behind me. A white sports car screamed past on the left and

I might have seen a hand gesture of encouragement thrust from his window over

the roof of his car.

My only regret is that I didn’t have time to sand and poly the

throne and put in a place of honor so that I could imagine Daddy was here with

his Bible and trombone celebrating Christmas with us. I know he is in heaven

playing with the heavenly choir, shaking that wrist for a special vibrato,

weaving his trombone in wide sweeps as the white clad choir members duck.